Its been a long time since I've written in my blog, and I have decided to revive it. Will you join me At the Table with Annie? As before, these posts will be musings on life, food and theology, but with a very specific direction for a time: the pilgrimage with Dante.

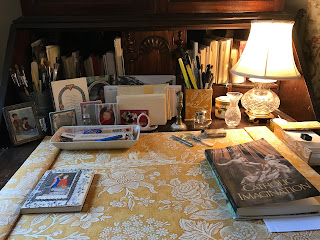

I'm writing from the secretary desk in my bedroom, which is a sympathetic spot possessed of outlook and comfort, and a certain amount of splendor, just enough to awaken the senses to Beauty, and hopefully not to dull them with over-indulgence. My desk is quite inviting, filled with all the little momentos that have made up a life thus far: photographs in little silver frames, letter writing supplies and a French blotter. Someday I'm going to have a big antique pine table as my desk, with a very simple white pitcher of garden roses for inspiration. As I have become older, my tastes have simplified and my aesthetic has become more relaxed. I have less need for the stuff that accompanies my journey, or perhaps life has edited the clutter, or I don't have as much need for props. That would be encouraging. But for now, this desk is a pleasant place to perch. Above me are shelves of books filled with many treasures marking other inquiries over the years. That, too, is an encouragement.

I spent the morning working in my vegetable garden, which I am reconfiguring this year to include planter boxes on either side of my parterre garden. I designed this vegetable garden with Andre' le Notre as my inspiration and guide: only the parterres are visible from the road, the rest of the garden hidden by a sleight of hand wrought of careful changes in elevation. This is not a bad metaphor for what I am undertaking in this blog: what is visible in life is only a very small part of the Real Story. The planter boxes have been built for me by my son to replace the French intensive row crops I have planted in the past, he having convinced me of the new plan's superiority. The sun is now out after a cloudy morning, and a cool breeze blows off the water and into the place where I live. I need the cool breezes today. Dinner is planned and prepped, and will be a savory clafoutis with leeks and corn and dark leafy greens served with an ombre heirloom tomato tartine with basil mayonnaise and cut into wedges.Today is cool and sunny, suggesting summer but not heat, so a baked clafoutis will not go amiss and the tomato tartan will still remind us that summer is upon us. These keepings are comforting in a world in flux.

It is with this flux, both in the world and in my life, that I begin my summer pilgrimage with Dante's Divine Comedy. I have most of my adult life cultivated a habit of choosing a summer reading theme each year. But this year, which has been especially challenging, it seemed more of a pilgrimage was in order, a kind of Way made by walking. You may know that this is the 750th year anniversary of the publication of this great work by a brilliant spiritual master. Dante Alighieri, the author of the Divine Comedy, was born in Florence in May 1265, and recently, even the Pope has heartily endorsed reading it as a spiritual guide in this commemorative year. It has been more than 30 years since I have read it, and when I did I was too young to understand it as a spiritual guide. I hadn't been battered about by life yet, and I was still largely living a charmed existence, and still pursuing existence before essence. But we'll get to Sartre later.

For most of my adult life, I have been fascinated by the concept of pilgrimages. This may be in part because of the long and arduous, yet spiritually rich trek my father and I made one year during a college summer on the Pacific Crest Trail throughout Oregon. We hiked 25+ miles a day with 50 pound packs, and it was arduous "walking" (as he called it), with little water, lots of heat, and little shade in some places. Yet, afterwards, I remembered only the things it taught me, save the red rock trails through part of Oregon, which I'll never quite forget. From the Middle Ages, the concept of a pilgrimage has tended to imply an endpoint or goal, such as a holy shrine that allowed the pilgrim to return home with a sense of accomplishment. I'll admit it: this has appeal. It is the appeal of the Camino, which I have longed to do since I first read about it 30 years ago. But the Celtic concept of pilgrimage, the peregrinate, is very different. It is not undertaken at the suggestion of a monastic abbot, for example, but because of an inner prompting in those who set out, a passionate desire or conviction to make an inner journey, wherever the Spirit might lead. Thomas Merton, one of my armchair mentors, taught his novices at his monastery at Gethsemene using Abraham as the exemplar of life as a journey: we go, leaving home, in search of God.

When I learned about Benedict's "Rule", which he wrote to inform the new monastic life he was founding, I, like Benedict, wanted to be a peregrine (purposeful wanderer), not a gyrovag (aimless wanderer). Sometimes, this necessitates a guide, rather like the map my father and I used when we "wandered" (his words, as if it were an afternoon stroll, hah!) on the mountain trails. And thus, my friend and I, who have for the past year "walked" our way through the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, have discovered that our pilgrimage was very rich indeed. (This was my forth time all the way through, and each time has been its own very distinct adventure.). Having completed the exercises, we looked about for another pilgrimage and decided to walk with the purposeful meanderings of Dante, who, at midlife, found himself in a dark wood, and embarked on a journey that rescued him from exile and saved his life.

And so opens the great epic poem: " Midway through the journey of our life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood, for I had wandered off the straight path." It's quite clear that Dante, having been battered by his Florentine life, having suffered political and personal ruin, and found himself exiled and alone, is facing a midlife crisis of the most profound sort. He writes that he finds himself in a wood of "wilderness, savage and stubborn," and that he found it a bitter place. Eventually, we all come to this place, however artfully we keep this abyss at bay. Recognizing that we are exiles in our own world is bitter indeed. It is also a sign of great hope, for it is the human condition we finally embrace. And from that first step sings a choir of Hope, painful though it is. Dante doesn't stop here, either. He writes that if he would show the good that came of this recognition, and of the place itself, he must talk about things other than the good. He realizes that he has become sleepy, having strayed and left the path of truth. But when he looks up, and raises his head momentarily out of his fear, he sees in the morning rays of light the planet that leads men straight ahead on every road. Hope. But we have only just begun to walk.

No comments:

Post a Comment